Museu da Imagem | Braga (Portugal)from November 9, 2013 to January 5, 2014Curator: Vítor NievesBubi Canal | Cecilia de Val | Damián Ucieda | Duarte Amaral Netto | Félix Fernández | Fernando Bayona | Florencia Rojas | Gonzalo Pérez Mata | Ixone Sádaba | Jesús Madriñán | Julia Montilla | Marta Moreiras | Marta Soul | Miguel Ángel Gaüeca | Rocío Verdejo | Rosa Muñoz | Sandra Torralba | Valentín Jaramillo

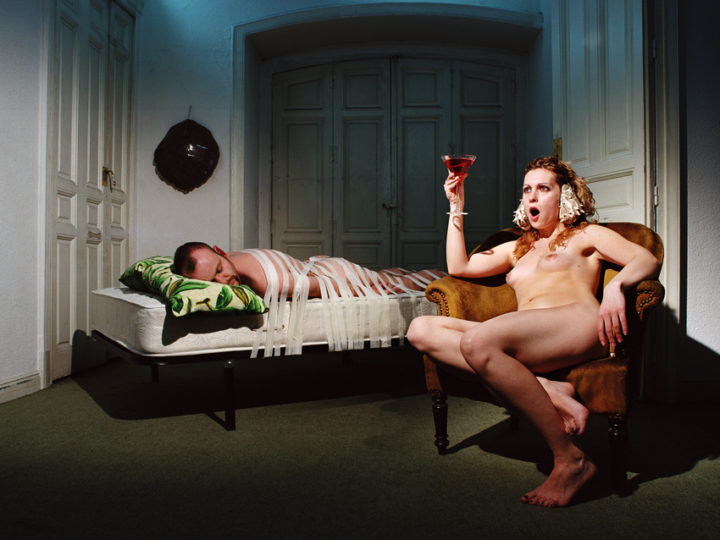

Don’t Look at My Camera is probably what the photographer-director would say to those who pose, just moments before the click, after their detailed work with props and lighting that define the pieces which form this exhibition. In all of them, recognizing the director of a single film frame as the one who calls the shots on all the visual elements that enter the plane, namely the people, chosen to represent a role.

The title of the exhibition makes reference to the link that is established between the photographer and the photographed and evidences the staging of the image. Thus lingers the latent footprint of the artist on their work, more than in any other photographic style, given that the codes of Staged Photography lead the artist, in the majority of cases, to portray themselves, guaranteeing their place in their created world, and, in some cases, ensuring their own permanence in art.

Throughout the 20th century the “New Vision” photographers, and also the surrealists, employed staging as a powerful creative style. These were the precursors of the so-called Staged Photography, a term which starts to be used with some degree of normality and assiduity in the decade of the eighties, paralleling the intensification of the debate about the validity and usefulness of documentary photography, since it is in this moment that it becomes apparent that, in photography, the threshold between reality and fiction is very narrow. Consequently, this type of photography diversifies and affirms itself as a genre undergoing exponential growth[1].

The photographers become directors and leave behind the notion of simply capturing reality for that of constructing it, opening a great window for fiction and calling into question the perception of reality.

Daily, in Staged Photography, the models are a primordial and crucial part of the structuring of the concept and composition of the image. Sometimes, it is the author who interacts and enters into their own work, even partaking in diverse roles, assuming fictitious identities. While other times, it is actors, actresses, or mannequins who, under the photographer’s direction, play roles, normally related to social life, or “status”, mythology, or dreams.

This photography field includes as well photography which excludes the human element, the staging is that of spaces, abodes, and cities. This is the case of Thomas Demand (Munich, 1964) and his work of reference, Office, where the photographed office creates tension in the viewer, who, upon seeing a completely realistic place, denotes certain nuances of unreality. Although they are less frequent, photographers who stage places without people have a similar modus operandi. Thus, the props and lighting are the main concerns which in large part occupy the artist’s studio hours, as in the case of James Casabere (U.S., 1953), who invents cities and villages with maquettes where the lighting has particular importance.

It is possible that one of the pioneers of Staged Photography is Oscar Gustav Rejlander (Sweden, 1813-1875) who, in 1957, publically presented his work The Two Ways of Life, which was the resultant image of montaging masses of photo negatives. Without a doubt, his personality and work were capable of influencing Henry Peach Robinson (England, 1830-1901), who photography historians archive in pictorialism, despite being an extraordinary reference in Staged Photography.

Nowadays, Staged Photography seems to be a trend among contemporaries, yet, if we thrash out the medium’s history, we see how photography has been staged since its birth and that staging has always played an important and decisive role. Hippolyte Bayard (France, 1801-1887), considered one of the fathers of photography, staged his own “postmortem” self-portrait, which seems to represent his failure in his intention to lead photography’s invention.

Today, Staged Photography enjoys wide acceptance in the art world, renowned figures work with the own codes of the genre, which has collected grammars from the language of advertising, painting, and cinema. Therefore, many creators work indistinctly in one or another discipline, as is the case of Erwin Olaf (Netherlands, 1959) and David LaChapelle (U.S., 1963), who are also advertising and fashion photographers, and whose commercial work merges, in a dangerously complicated web, with their artistic work. LaChapelle, moreover, has created various audiovisual works as a filmmaker (namely video clips of American celebrities). Study of lighting, stage, and model directing has also served Cindy Sherman (U.S., 1954) to work in cinema.

Erwin Olaf, perhaps greatly influenced by having his Amsterdam studio in a church and being surrounded by religious imagery, reflected back on his own work, which more and more dealt with such human themes like sex and death. However, Olaf’s definitive jump towards Staged Photography came with the arrival of digital photography. Considering what he responded in an interview done by a Dutch television channel, he reveals that the process of digitalization allows a complete control over the final work, analogous to what happened with traditional black and white photography. His work is conceptually very pictorial and formally very cinematographic. Something very visible in Olaf’s work, and applicable to many creators of Stage Photography, is the sense of humor that verges on kitsch, and, sometimes proves even iconoclast. Indeed, his recurrent theme, in an initial phase, is also common to many creators: sex and sexual identity is the main focus of many of these photographers, so much so that in the artistic studies of gender, above all, those areas related to LGBT rights proclaim Staged Photography as an exclusive communicative expression of their own.

Very similar to this work, as earlier written and now reiterated, is that of LaChapelle, but from a more “pop” and colorful perspective, and with a relentless obstinacy for making iconoclast images that call into question the figures of American entertainment, with constant allusions to consumerist society and the major brands, which appear depicted as mainstays of society as a whole, but that stifle individuality. Although he has meshed his commercial and artistic work for major weekly fashion publications, much of his work has a very explicit critical capacity which is very related to his Latin American origins, a people who tries to integrate themselves by digesting everything the American system spits out, despite being themselves excluded.

In this quick overview of Staged Photography, it is imperative to name those creators who, being far away from advertising, do more conceptual work, like the forenamed Sherman or Jeff Wall (Canada, 1946), with clear intentions in each image they create.

However, Staged Photography can also be conceived to call into question the popularized concepts on which journalistic and documentary photography rely. This is the case of Joan Fontcuberta (Catalonia, 1955) which disrupts the rationale of those that ascertain that photography portrays reality. His projects, whether inventing stories to publish them as true in the media, or creating volumes and archives of flora which never existed, involve staging whose objective is to create images which reflect upon photography as a medium.

The representation of oneiric worlds has also been characteristic of Staged Photography, ever since the advent of surrealism. Two bodies of work which serve as examples of two distant extremes are that of Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison (U.S., 1968, 1964), related to the dialectics of children’s stories, and that of Ouka Leele (Spain, 1957), tainted by the aesthetic of a Madrid awoken from a long dictatorship.

Sometimes, the Western and androcentric perspective of the history of photography, left out creators like the Countess of Castiglione (Italy, 1837-France, 1899), who, strictly speaking, was not a photographer, however, took great pleasure and care in staging and lighting photographs to, subsequently, according to her indications, be portrayed by Pierre-Louis Pierson (France, 1822-1913). Certainly, her work served as a reference for that of Gregory Crewdson (U.S., 1962).

As in the critical capacity that, as previously mentioned, manifests itself in the work of Olaf, there is a certain didactic vein in the work of Carrie Mae Weems (U.S., 1953), a photographer almost unknown in Europe, who works with expressions of African-American culture, in a discourse that gives coherence to the different and multiple photographic areas in which she works.

Originating from Russia, the collective AES+F (Tatiana Arzamasova, 1955; Lev Evzovich, 1958; Evgeny Svyatsky, 1957; and Vladmir Fridkes, 1956) managed to transcend with their photographs the closed Russian art world, with images that remind us of videogame screenshots, in their own staging of post-apocalyptic, futurist films.

Marcos López (Argentina, 1958) is another creator who employs kitsch stylistically, like LaChapelle, to construct images in which color works to perfection, making small studies that question certain customs of modern society. Another author who is quite distant from López, but who works closely with the traditions of Latin America, is Luis González de Palma (Guatemala, 1957), who, with a historical photography aesthetic, achieves images that do not go unnoticed by the common viewer.

The intrinsic characteristic of photography is its ability to document, yet it is something that, in many countries, is already in disuse, like in China, where documentary photography is considered obsolete. One reference in the East is Yasumasa Morimura (Japan, 1951) who achieves the redundancy of Staged Photography, who works in the game of staging the staging: working with images that are iconic in the West, and which were previously staged, reinterpreting them from an iconoclast point of view and with an Eastern sense of humor hard to understand in the West. The work in which the clear reflexivity of Staged Photography can be seen is that where he photographs himself imitating a photograph of Cindy Sherman.

Don’t Look at My Camera is configured with works from various creators who are quite different from each other, yet showing what unites them. The control of the lighting, the direction of the figures, the staging of the environments and the references to the lengthy stories that each image communicates, may reveal that Staged Photography is the product of a desire to control a reality that escapes us, yet which we can photograph, therefore, consequently, that moment was made a reality, in spite of its ephemeral nature.

Vítor Nieves. Curator

[1] Momentos Estelares de la Fotografía del s.XX (Stellar Moments in Photography of the 20th century). Oliva María Rubio. Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid. Chapter “Puesta en escena (mise-en-scène)”.

Opening of the exhibition and statements by Vítor Nieves (curator) and Rui Prata (director of the Museum)